Voicing rules. Adjectives. Expressing Possession (У меня есть)

At this point, we have learnt almost all the basic pronunciation rules, but you could have noticed that some pieces of a puzzle are missing, like in the following examples:

О́чень рад! Рад познако́миться! До встре́чи! В контакте. Всё в поря́дке.

Здра́вствуйте!

Что, потому́ что, коне́чно

Его́, всего́ хоро́шего, до́брого дня, etc.

In this lesson,

- we’ll learn two voicing rules in Russian: word final devoicing and voicing assimilation;

- we’ll see some important pronunciation “deviations” (which are rather exceptions than rules);

- You’ll discover how to use adjectives, how to change their endings for the genders;

- We’ll learn how to express possession with the equivalent of the English verb “to have” (I have = У меня есть), for example when talking about family members, pets etc.

Consonants losing their voice

Some consonants (б, в, г, д, ж, and з) are voiced consonants because they’re pronounced with the voice.

But when these consonants appear at the end of a word, or precede a voiceless consonant (п, ф, к, т, ш, с) they lose their voice. This process is called devoicing. They’re still spelled the same, but in their pronunciation, they transform into their devoiced counterparts:

- Б ⇒ П зуб [п], но зу́бы

- В ⇒ Ф ав[ф]то́бус, но ава́нс

- Г ⇒ К друг[к] , но друго́й

- Д ⇒ Т го́род[т] , но города́

- Ж ⇒ Ш нож[ш] ,но ножи́

- З ⇒ С моро́з[с] , но моро́зы

This will also occur across word boundaries: the phrase “in Canada” in Russian—“в Кана́де”—will be pronounced [f ka‘nadje]; the [k] influenced the [v] to become devoiced and pronounced as [f].

“До ско́рой встре́чи” (See you soon) – a song by ЗВЕРИ

The voicing rule also works the other way round, resulting in a voiced consonant influencing voiceless consonants to become voiced: с[з]дача, с[з]делать, вок[г]зал, от[д]дыхать, фут[д]бо́л etc.

Вот ва́ша сда́ча. (Here’s your small change)

На́до э́то сде́лать. (It should be done)

Здесь есть вокза́л. (There is a train station here)

Я люблю́ отдыха́ть до́ма. (I like to rest at home)

Я люблю́ игра́ть в[ф] футбо́л. (I like to play football)

Words like ‘что’

including expressions containing it (что́бы, ко́е-что́, что́-то, ничто́; потому́ что; не́ за что) and ‘коне́чно’ are pronounced with ‘шн’ and these are actually exceptions, just to be memorized.

There is no hard and fast rule where чт / чн should be pronounced as its written, i.e. with ‘ч’ (почти́, не́что; то́чно, моло́чный) and where ‘ш’ must appear (ничт[шт]о́; коне́чн[шн]о).

Likewise, there are words where both variants of pronunciation are acceptable:

“бу́лочная (чн)” и “бу́лошная (шн)” – bakery

“ску́чно(чн)” и “ску́[шн]о” – boring ([шн] is the correct way to pronounce, though it’s very common to hear [чн]-version)

(“Our people don’t take a taxi to the bakery”, a scene from “Бриллиантовая Рука” – The Diamond Arm, 1969)

(The word for “what” is “что”. But as a slang it can be pronounced as “чё”; a scene from “Джентельмены Удачи” – Gentlemen of Fortune, 1971).

(A scene from “Служебный Роман” – Office Romance, 1977).

The letter ‘г’ pronounced as [в]

In a few words the letter г is pronounced [в]. For example, the possessive pronoun his is spelled его́ but pronounced [йиво́]; the word today is spelled сего́дня but pronounced [с’иво́дн’ a]; the genitive case adjectival endings are spelled –ого, –его but pronounced [- в ], [-иво/-ив ]

Всего́ хоро́шего! До́брого дня!

In a root ‘г’ is pronounced [г]. For example, men’s name Его́р sounds [йигор], the adverb meaning much/many мно́го [мно́га].

– Как зовут твоего русского друга? (What is your Russian friend’s name?)

– Его зовут Егор. (His name is Yegor.)

Pronunciation of –тся and –ться endings of some verbs

‘-тся‘ and ‘-ться‘ endings of some verbs and verb forms are always pronounced / ца / [tsa].

For example,

Прия́тно познако́миться ( Nice to meet you).

Мо́жно оста́ться? (May I stay?)

Находи́ться – он/она/оно нахо́дится (is situated, is found) – они нахо́дятся (are situated, are found) (be, stay (somewhere, in some condition); be situated)

Называ́ться – он/она/оно называ́ется – они называ́ются (to be called: about inanimate objects, words, places, etc.)

- Как это называ́ется? Как называ́ется эта улица? Где она нахо́дится?

Две́ри закрыва́ются (the doors are closing)

По́езд отправля́ется (the train is departing)

“Silent” consonants

There is a limited number of words in Russian where there are “silent” letters (consonants) that are not pronounced, such words are to be memorized. Here are some of the examples:

Здра́вствуйте! (hello)

Чу́вство, чу́вствовать (feeling, to feel)

- Как вы себя́ чу́вствуете? (How do you feel?)

Где ле́стница? (Where are the stairs?)

Я не ме́стный (I am not local)

Я сего́дня ра́достный, потому́ что со́лнце све́тит. (I am cheerful today because the sun is shining)

Се́рдце (heart)

По́здно (late)

- лу́чше по́здно, чем никогда́ (better late than never)

- ра́но или по́здно (sooner or later)

- Пра́здник (holiday, celebration, special day)

– У вас сего́дня како́й-нибудь пра́здник? (You have some occasion to celebrate today, don’t you?)

– Экза́мен для меня – всегда́ пра́здник, профе́ссор. (An exam for me is always an occasion to celebrate, Professor)

Decorating Your Speech with Adjectives

An adjective is a word that describes, or modifies, a noun or a pronoun, like good (хоро́ший, до́брый), nice (прия́тный, краси́вый), big (большо́й), small (ма́ленький) etc. In English, an adjective never changes its form no matter what word it modifies or where it’s used in a sentence, but a Russian adjective always agrees with the noun or pronoun it modifies in gender, number, and case.

- Прекра́сный вид (Masc., Sing., Nom. case)

- Замеча́тельная фотогра́фия (Fem., Sing., Nom. case) – замечательные фотографии (Pl., Nom. case)

- Лётное по́ле (Neut., Nom. case)

- Социа́льная сеть (Fem., Sing.,Nom. case) – социальные се́ти (Pl., Nom. case) – для социальных сете́й (Pl., Gen. case)

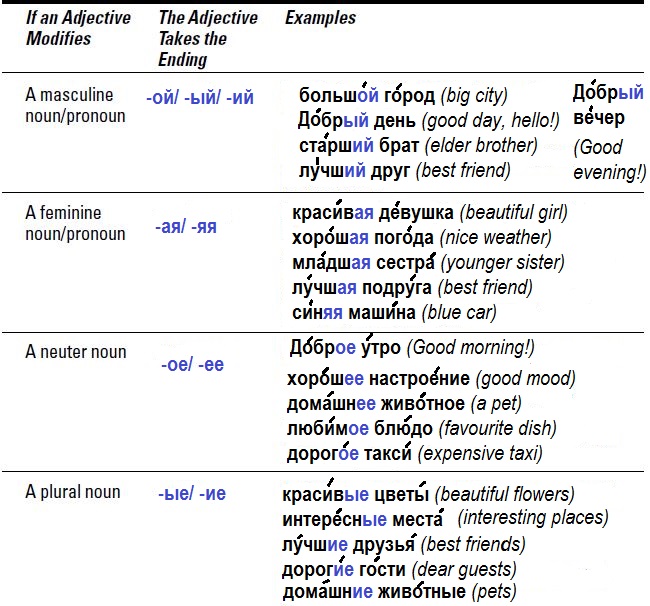

Table 1.

Putting the rule to work, the first thing to do is (!)to figure out the gender and/or the number of the word which your adjective defines. (In plural, there is no gender distinction: there are no gender-specific word endings!)

Then (!)adjust the ending according to the present grammatical structure (Gender – Number – Case).

How to choose the right ending when there are at least 2 of them for each gender?

*In my lessons, I explain this rule showing a number of examples that make it clear.

- Read this text and retell it.

Петербу́рг — большо́й и краси́вый го́род. Он не о́чень ста́рый. Здесь е́сть но́вые проспе́кты и ста́рые у́зкие у́лицы. Гла́вная у́лица — Не́вский проспе́кт. Он дли́нный и широ́кий.

- Create a similar text about your city/town (го́род) or village (дере́вня).

- Read the following description of a room. Complete it with suitable adjectives from the Word Bank below putting them in the right form. Then you can check your variant with the audio track. (In some cases, more than one option is possible).

Э́то моя́ ко́мната. Она́ (…..) , но (…..) и (…..) . Тут мой (…..) дива́н, а здесь мой (…..) телеви́зор. Сле́ва мой (…..) стол и моё (…..) кре́сло. Спра́ва мой (…..) шкаф. Там (…..) оде́жда. Вот моя (…..) крова́ть. А вот моя (…..) по́лка. Тут мои (…..) книги.

Word Bank: большо́й, пи́сьменный, кни́жный, огро́мный, све́тлый, удо́бный, мя́гкий, небольшой, ую́тный, но́вый, ра́зный, люби́мый.

Talking about what you have

When talking about your family, for example, use phrases like “I have a brother”, “I have a big family”, etc. In Russian, the verb “to have” is “име́ть” but its use is rather limited. Instead, what is commonly used to expresses possession is the following construction:

For example, in the sentence “У меня́ е́сть (огро́мная) семья́”(“I have a (huge) family”), the owner is expressed by the prepositional phrase “У + a noun/pronoun in the genitive case” (meaning literally “at somebody”), followed by “есть” (there is), and the object of possession is expressed by the noun or phrase in the nominative case.

The resulting Russian sentence: “У меня есть (большая, огромная) семья” can be literally translated into English as “At me there is a (big, huge) family”.

As to the interrogative sentences, you form your question as if you were making a statement (bearing in mind that there is no inversion, no auxiliary verbs!) – it’s enough to change your intonation.

У меня есть хвост. → У меня есть хвост?

If you want to say that you don’t have a brother, a sister, a nephew, and so on, you use the construction “У меня нет” plus a noun in the genitive case (will be explained in the following lessons).

Sometimes, the word “есть” is omitted.

- У вас сего́дня како́й-нибудь пра́здник? (Do you have some occasion today?)

Generally, you should use “У меня есть …” to say about actual possession (having relatives, friends, objects). You can omit есть when, for example, it already has been used in the first sentence, so it is simply implied.

- У меня есть каранда́ш (I have a pencil). – А у меня ручка. (And I have a pen)

- У вас есть о́пыт рабо́ты? (Do you have work experience) – У меня большой опыт работы. (I have extensive work experience)

There are cases where using or omitting есть leads to different meaning or implication of the phrase. It can be confusing because in English and other languages there is the verb (e.g. to have).

You should use “У меня …” (есть) :

- to point to qualities, features of the objects, etc. you have, rather than the object itself:

У меня чёрный Мерседе́с. – I have a black Mercedes (that is to say what kind of car you have).

У меня замеча́тельные друзья́. – I have amazing friends.

У меня чёрное пла́тье. – I have a black dress.

In this case, is not just stating a fact of ownership, but emphasizing the consequences or implications of having something. Still, you CAN use есть in such sentences, but the meaning will shift to merely stating the fact of possession. (Even though it may seem baffling and bewildering in the beginning, better understanding will come with practice 😉

There are cases where you just don’t use есть altogether. For example, we always omit есть:

- to talk about plans, appointments, festive occasions, etc.:

У меня пра́здник. – I have a party.

У него́ cвида́ние. – He has a date.

- to talk about your appearance:

У меня голубы́е глаза́. – I have green eyes. - to talk about states of mind and illnesses:

У меня грипп. – I have a flu.

У меня температу́ра. – I have a [high] body temperature.

У меня депре́ссия. – I have depression (I am depressed).

У меня хоро́шее настрое́ние. – I have a good mood (I am in a good mood).

- Describe your family. (У вас большая семья? У вас есть брат и / или сестра? У вас есть муж или жена? У вас есть дети (сын и / или дочь (дочка)? У вас есть бабушка и дедушка? У вас есть дядя и тётя? У вас есть домашние животные (кот, собака)? Как их зовут?

- Describe your room. (У вас большая комната? Что там есть?)